The Comparison Fallacy in Crypto

Why Investors Shouldn't Evaluate Web3 Companies from a Web2 Lens

One of the most salient lessons I’ve learned from investing in crypto startups is this: evaluating a crypto company through the lens of its Web2 counterpart is often fallacious. Just because a category yielded a billion-dollar outcome in Web2 doesn’t mean its crypto equivalent will follow the same trajectory—and conversely, the crypto-native version of a failed Web2 startup might turn out to be a breakout success.

In my experience, these comparisons tend to fall into one of two buckets:

Crypto GOATs Born from Web2 Duds: a breakout success in a stagnant Web2 sector, where crypto-native mechanisms unlock entirely new growth dynamics.

Crypto Duds Born from Web2 GOATs: a failed attempt to replicate a dominant Web2 business model, where fundamental structural differences in crypto break the very assumptions that made the original work.

First Bucket: Crypto GOATs Born from Web2 Duds

In crypto, some of the most compelling use cases emerge when a Web3-native approach redefines a plateaued Web2 category. These aren’t just crypto clones of existing Web2 products—they’re fundamentally different bootstrapping machines that unlock entirely new demand curves. By embedding crypto incentives into go-to-market strategies, these projects solve the cold-start problem and activate users in ways Web2 cannot.

Take Worldcoin as an example.

The identity sector in Web2 is mature and heavily consolidated. Enterprise platforms like Okta, Microsoft Entra, and Google dominate. Power is too concentrated in platforms & access to user data is almost entirely walled-off. Any startup aiming to build a user-owned identity graph from scratch faces near-insurmountable barriers.

Yet Worldcoin did it. Within its first 6–8 months, it onboarded over 10 million users across 160+ countries, collecting one of the most sensitive data types—retina scans—at global scale. For a Web2 identity startup, this level of adoption would require years of compliance vetting, trust-building, cross-border partnerships, and user acquisition spend.

So why did it work? The answer lies in a user-incentivization loop that only crypto can create.

Worldcoin designed its reward structure to front-load user reward through a tapering emission schedule. At launch, users received up to 25 WLD as a “genesis grant,” with ongoing monthly rewards starting at ~3 WLD and decreasing over time. This created urgency—early users earned more for the same action—and a clear countdown effect that pulled forward demand.

One might argue that Web2 startups could also just pay users like this. But there are two critical distinctions:

User Subsidies Funded Externally (by the Liquid Market) in Web3 vs. Internally (by the Company) in Web2

Worldcoin distributed over 525 million WLD tokens. During the early distribution window, WLD traded between $3–$10, equating to $1.5B–$5B in value delivered to users—without the company spending from its balance sheet. These weren’t coupons or ad credits. They were liquid assets, priced and distributed by the open crypto market. In Web2, only hyper-capitalized companies like Uber have executed user acquisition at this scale, and it was entirely funded through venture dollars from investors, costing billions in cash burn.

Crypto uniquely gives startups access to tap external liquidity from the crypto capital markets at previously unfathomable scale to overcome the cold start problem—without diluting equity or draining treasury.

Crypto Automatically Turns Users into Stakeholders

A user on Instagram doesn’t necessarily care about Meta’s share price unless he/she bought the stock separately. But when a user receives a Worldcoin airdrop, they are automatically financially tied to the network’s success. That alignment changes behavior: users become active promoters, referring friends, defending the project, and contributing to its growth.

A key reason this works is that token incentives are dynamic, not fixed. In Web2, referral rewards are typically static—$10 is always $10. But in crypto, 15 WLD could be worth $5-$150, depending on market performance. This price variability amplifies emotional and financial engagement. Users don’t just earn—they speculate, evangelize, and stay invested. Their upside is no longer capped.

In essence, tokens are more than just rewards—they are a viral, financial coordination mechanism, turning users into an organic, decentralized marketing engine fueled by ownership.

The “Self-Fulfilling Effect” of Token Networks

Beyond a customer-acquisition hack, the crypto component can also be a powerful engine for sustainable user growth past the initial phase. A token network creates a reflexive loop between belief, participation, and value—a phenomenon I call the Self-Fulfilling Effect. In this loop, belief itself becomes an active economic force: it bootstraps supply, demand, and legitimacy simultaneously.

Take Offline Protocol as a current example. It aims to build infrastructure and applications that function without internet or traditional telecom—a radically contrarian bet on the future of sovereign, offline connectivity.

Here’s how the self-fulfilling dynamic plays out:

If I believe that offline-first infrastructure will be essential

→ Then my Offline ID and token could become valuable

→ That belief drives me to participate early—to farm, test, refer

→ More users = more local nodes = more utility

→ That utility reinforces belief, and belief accelerates adoption

The result is a self-reinforcing flywheel leading up to 300k+ organic signup with zero marketing dollar. Tokens don’t just represent value—they create it, by giving users a financial stake in a future they actively build.

This isn’t new. Bitcoin is the canonical example of the “Token Self-fulfilling Prophecy”. In its early days, miners believed Bitcoin could become a store of value → they mined despite low rewards → belief spread → more miners joined → hashpower increased → security improved → institutional belief followed → price rose. A belief loop became a value loop.

Tokens are more than incentives—they are economic coordination tools that drive belief, behavior, and growth at the same time.

Second Bucket: Crypto Duds Born from Web2 GOATs

I have yet to see many crypto skeuomorphs of successful Web2 companies achieve resounding success. Projects that set out to become the “Google, Snowflake, Amazon, Facebook of Web3” have largely fallen short.

Maybe Binance comes close to playing the “Nasdaq of Web3,” but that’s a rare exception.

Why is that?

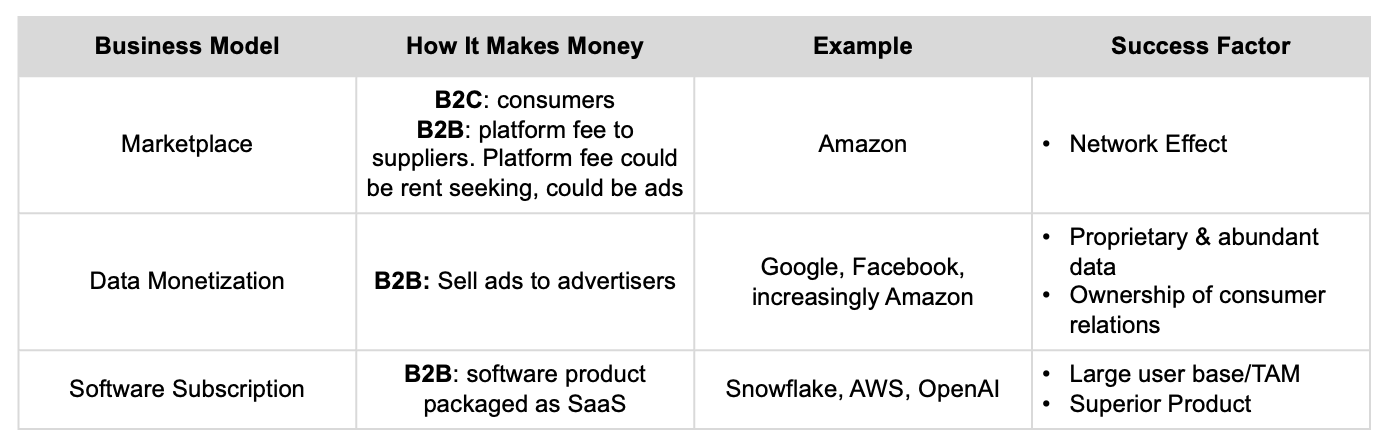

My hypothesis is that what made the magnificent 7 so dominant was Business-to-Business-Model Fit as below. Let’s examine three dominant business models from Web2—Marketplace, Data & Attention, and SaaS—and why their Web3 counterparts faltered.

1. Marketplace Business Model

Web2 Example: Amazon, Airbnb, Etsy, Uber

Monetization:

B2C: Transaction fees, markups on sales

B2B: Ads, platform fees from sellers

Success Factor: Strong network effects—more buyers attract more sellers, creating scale-driven defensibility. Such network effects create sticky, winner-take-most platforms. More users = more value = higher switching costs = lower acquisition costs.

However, in crypto, Network Effect does not work due to below three structural differences:

Crypto Users Tend to Be Mercenary: Developers treat chains like products—choosing based on fees, speed, liquidity, and grants. Retail users chase yield and slippage, not UX or brand. Validators stake where reward is highest. Loyalty doesn’t factor in.

Crypto is open-source by default, which drastically lowers the barrier to entry for copycats: Anyone can fork. SushiSwap copied Uniswap’s code and UX, then added better token incentives to drain users—a “vampire attack” that would be impossible in Web2 without stealing Facebook’s entire backend and bribing users to move.

Crypto is interoperable by default, which minimizes switching costs for both developers and retail users: Swapping USDC to USDT or PYUSD takes seconds. On the other hand, switching a card from the Visa network to Mastercard is much more onerous.

❗️In some cases, it can even be argued that crypto has the opposite of the Network Effect: more users = lower yield (in DeFi) or higher gas fees (on congested chains).

As a result, while the marketplace model has been responsible for some of the most successful web2 tech giants, it is not a defensible business model in Web3—because it relies heavily on the network effect, which fundamentally does not hold in crypto. For a deeper look at why the network effect breaks down in crypto, see this deep-dive piece.

2. Data & Attention Business Model

Web2 Example: Google, Facebook, ad-driven publishers

Monetization: B2B: Sell access to user data via targeted ads

Success Factor: Proprietary data and ownership over user relationships

However, proprietary data or “data moat” simply doesn’t exist in the onchain world. Everything on-chain is fair game and accessible to everyone. One could argue that there are data moats to be had from:

Organizing and structuring on-chain data, and competing on the quality of such service (e.g., indexing protocols)

Combining on-chain and off-chain data (since most metadata—such as customer information, content, etc.—is stored off-chain), which can be proprietary

Sure, but to monetize data, this on-chain + off-chain combination would need to be made “proprietary” and closed (e.g., Chainalysis), which inherently contradicts Web3’s ethos of transparency and decentralization.

Also, the degree of exclusivity or proprietariness of data—which often serves as a proxy for its implied value to potential data buyers—is much lower in Web3. Facebook has complete monopoly over its customer data, giving it absolute pricing power.

By contrast, even one of the most lucrative data companies in Web3, Chainalysis, faces fierce competition from TRM Labs. Chainalysis may maintain competitive presence due to feature depth, oversight, and UX—but it still works off the same on-chain data out in the open as its competitors.

3. Software Subscription (SaaS) Business Model

Web2 Example: Snowflake, Salesforce, AWS, OpenAI

Monetization: B2B: Subscription-based recurring revenue

Success Factor: A large user base + a superior, sticky product to generate predictable recurring revenue and low churn.

SaaS has been the crown jewel of software business models over the past decade. Its success—valued at $384B in 2024, projected to exceed $1.8T by 2034—comes from:

Massive TAM: virtually every company across sectors—finance, logistics, healthcare, media, government—benefits from SaaS. It addresses nearly the entire GDP.

Accounting benefits: predictable recurring revenue, OPEX vs. CAPEX shift, easier budgeting.

Operational efficiency: reduced IT overhead, faster onboarding, better infra management.

Financial clarity: subscription-based revenue, high margins, and cost predictability at scale.

In contrast, Web3-facing B2B SaaS serves a much smaller economy. For a Web3 SaaS company going to market, the pool of potential buyers is hyper limited. Outside of giants like Coinbase or Binance—who are actually more likely using mature Web2 software stacks for IT management, most Web3 companies lack enterprise-grade spending power. These teams are lean, often pre-revenue, and operate with limited software budgets. Formal procurement processes, such as multi-year contracts, are nearly impossible.

Of course, one could argue that a Web3 B2B SaaS company can still target the broader Web2 enterprise space—yes, theoretically. Several counterarguments that make it infeasible are:

Web2 enterprises sales requires a completely different skill set and salesforce than selling to Web3 startups.

Few Web2 enterprises are adopting truly crypto-native or on-chain products, as blockchain is not yet core to their business operations.

Competition in the Web2 SaaS space is far more intense, with a full suite of well-established startups that often deliver superior UX and enterprise readiness.

Now, what are unique moats in web3 warrant a separate article for another day.